More Than Words: An Autism Journey

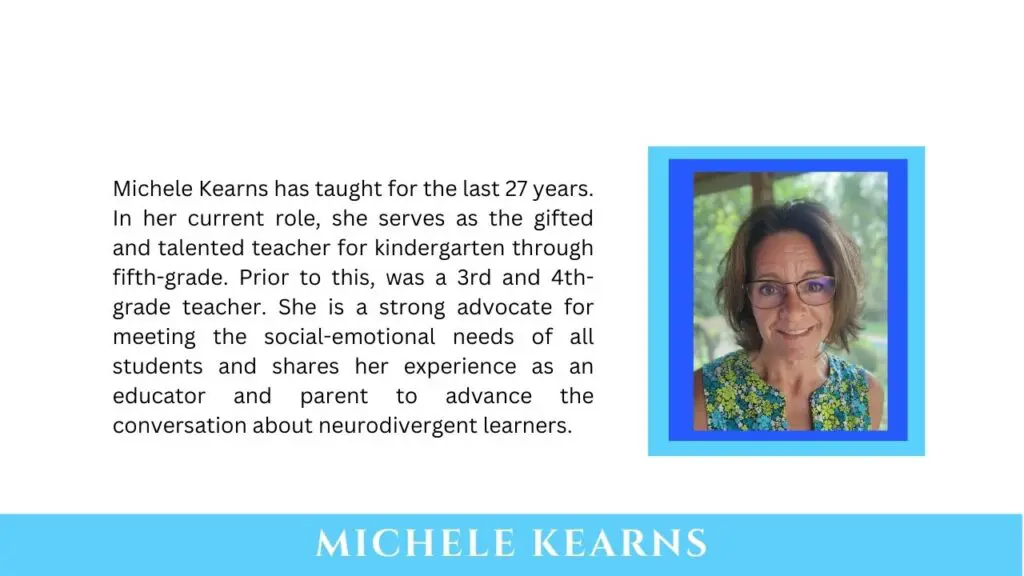

By Michelle Kearns

A picture is worth a thousand words—except this one. He didn’t have a thousand words. Maybe he did, but he couldn’t express them. Instead, he used his hands—six-year-old hands, flapping as fast as they could, his mouth open wide, eyes locked on the horizon as the sand and ocean met his feet. I didn’t need words. In that moment, all the tests, therapy, hospital visits, and fears for the future rolled out with the tide. Peace washed over him, calming his excited little body, and my spirit was quiet for the first time in years. This was a defining moment in our autism journey.

Beyond the Puzzle Piece

When you see a colorful puzzle piece, what comes to mind? As an educator of 27 years, I find this answer easy—autism awareness, especially in April. In a world with one in 36 children diagnosed with autism, this would be a common and relatable response. As a parent of a child with autism for nearly 16 years, this response seems insufficient.

I’ve heard it said, “If you’ve met one person with autism, you’ve met one person with autism.” What does that really mean? It means no two journeys are the same; no single book or expert holds all the answers. The story is constantly being written, updated, and rewritten.

At first, I approached this blog from a professional lens—how educators can support and relate to autistic students. I included research, strategies, and catchphrases to provide meaningful information to help others develop as educators. But a friend reminded me that my son, Gehrig, and I have a story to tell. So, walk with me for a moment as I tell you our story.

Not Knowing What You Don’t Know

With four kids in six years, I thought I had parenting figured out. I was wrong. I had no idea my youngest child would be the one who taught me the most in life, and I don’t mean how to parent. Early on, we knew something was different about Gehrig. He barely hit his developmental milestones, leading to countless doctor appointments, tests, specialists, and brain scans.

The day we received the call from the Head of Neurology at Children’s Hospital would be the first time my husband and I fell to our knees in prayer for our son. We heard the doctors on the other end mention things like“Too much gray matter.” “Shortened life expectancy.” “Let’s reassess at age two.” A year! What? So we did what any other parent in that position would do, we handed it over to a higher power and sought early interventions to give him the best chance we could since we didn’t know what we were up against. My weeks consisted of teaching during the day and visits with physical, occupational, speech, and language therapists while my husband (a school principal) juggled our other three children. We enjoyed as much as we could of what our sweet boy could tolerate, and eventually, the year passed.

The second time we fell to our knees was after Gehrig’s second birthday when we received his diagnosis—autism. Autism? Praise God!! Even as educators, we didn’t know much, but we knew, as parents, we would find a way to learn what we didn’t know about autism.

We would learn that children with autism, especially toddlers and young school-age children, often have no sense of fear. Consequently, they elope and wander with no regard to safety. We fundraised for a service dog through 4 Paws for Ability to combat this fearlessness. Frodo was trained for nearly 18 months to tether to Gehrig, track him if he went missing (which he did), and provide comfort during meltdowns. Frodo kept Gehrig calm when his environment overstimulated him. While Frodo was prepared to attend school with Gehrig, incredible educators, interventions, and IEP goals helped Gehrig navigate the classroom successfully.

We soon learned that Frodo was more than a safety net. He gave Gehrig something to talk about. Talking can be a challenge for individuals with autism, especially when they are young. Receptive and expressive language is often unequal in people with autism, even if they understand more than they can say. Part of building a relationship with autistic individuals is bridging this gap, which requires simple strategies. We shared strategies with Gehrig’s teachers, and talking about Frodo proved to be Gehrig’s outlet.

His teachers embraced simple strategies like

- Be patient in conversation, allowing extra time for responses.

- Provide a calm, structured environment free of overwhelming distractions.

- Learn and engage with their favorite topics.

- Help sustain conversations by suggesting topics or choices.

- Redirect with gentle prompting when they speak at length about interesting topics.

For Gehrig, Frodo was the gateway to words. Later, it became maps, directions, and game shows.

Understanding and Including

It became our goal to teach everyone we knew about autism, starting with our own

family. Fortunately for our family of six, we already had well-established routines with our other three children because our parenting style doesn’t include chaos, yelling, or raised voices, nor is it one of inappropriate language. This made our household environment a good place for Gehrig. Consequently, this same reality made growing up with a sibling with autism look easy or simple for our other three children to outsiders. Adding an autistic little brother had moments of difficulty for them, but they made it appear effortless.

If you ever want to see how a person with autism should be treated, just look at Gehriig’s siblings. Our four children couldn’t be more different, and that has nothing to do with autism. But they handle one another, from adolescence into adulthood, with the respect, love, and trust modeled for them. Sure, there has been sibling rivalry and all the typical features of growing up in a large family, but their protection of Gehrig and desire to make him belong within their friend groups has been a model to anyone who steps foot in our home. As a mom and educator, I ultimately hope to provide the same classroom setting for all our students.

Step outside of our family, however, the stigma of autism itself proved that awareness was not enough. When we shared Gehrig’s diagnosis, people responded apologetically, almost with grief. To give him the best quality of life we could, we would have to get uncomfortable with others, and we would have to make him uncomfortable sometimes as well. None of it would be easy, but it would all be necessary. We quickly learned acceptance was our new goal and needed to change the narrative.

We took Frodo with us when we went out in public, and Gehrig would talk more with strangers who wanted to pet his service dog. This provided an opportunity to educate others on autism, moving past awareness and to acceptance, knowing inclusion and belonging would be the ultimate goal. But these were brief, fleeting moments on this path. We needed something more sustainable, specifically with his peers.

An instrumental cog in the wheel of autism acceptance we couldn’t do on our own was including him in activities with other kids. In a classroom, IEPs and 504s can help students with autism find success, but they rarely allow them to form meaningful relationships with peers. As educators, we know that not all students thrive academically, but most kids have something in common: play. As kids move up in school, play is limited and eventually removed from the academic day; however, if their classroom teachers have built and modeled relationships with them, their peers will include them if given the opportunity. We could educate and advocate for this but couldn’t guarantee it, so we knew we had to find a way to fill this gap.

One such opportunity was when Gehrig played Challenger Baseball with other individuals with disabilities. Neurotypical peers volunteered as “buddies,” and they were often classmates or members of the school community. He loved being on the field with all of these new friends! His buddy would help him understand the rules of the game while keeping him safe and stood right beside him as he played. Many communities offer “Challenger” sports, such as baseball, soccer, and basketball for individuals with disabilities

However, he would thrive in one setting beyond our wildest expectations.

Belonging: The Universal Language of Sport

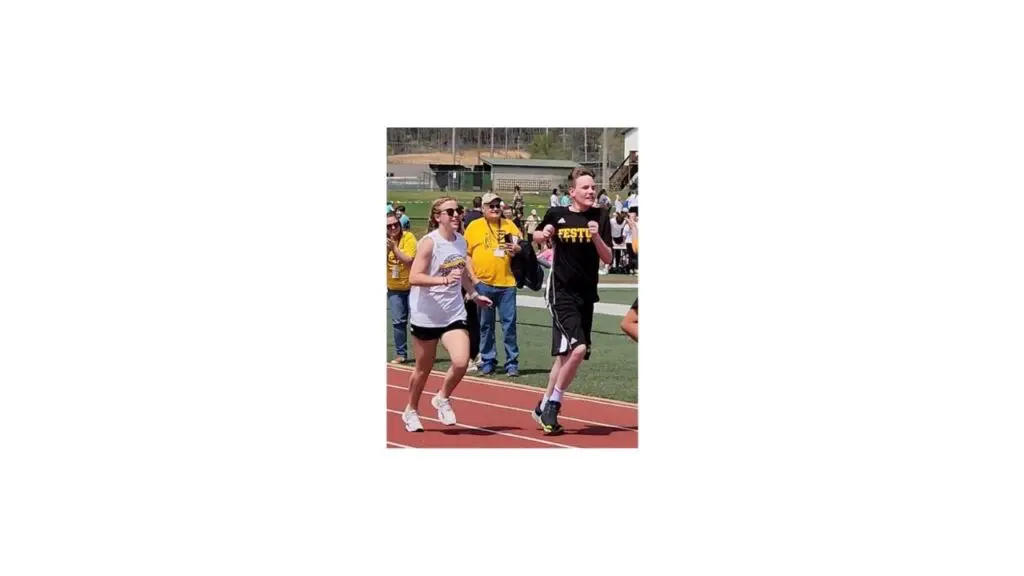

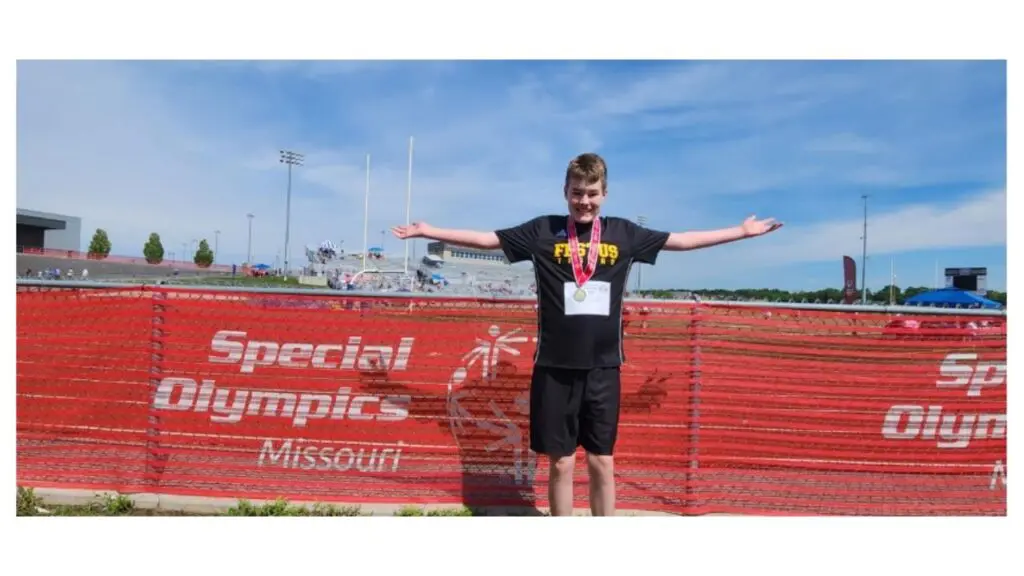

Like many children with autism, Gehrig faced motor skill challenges addressed through years of physical and occupational therapy. He wouldn’t be the fastest runner or strongest thrower, but he fell in love with both when he was introduced to the Special Olympics.

Inclusive play removes the pressure of academics and allows autistic students to connect with peers naturally. Programs like Special Olympics and Play Unified give neurodivergent students a sense of belonging. Inviting neurotypical peers to participate in pick-up games of basketball, or even board games or video games, with neurodivergent classmates based on their interests cultivates an environment of acceptance. It allows autistic students the comfort of sharing preferential activities and engages them with their peers in a setting that encourages true inclusion and, dare I say, belonging.

I won’t say all the puzzle pieces of awareness, acceptance, inclusion, and belonging are perfectly placed, but our family continues to push toward our goal. Each year, we witness and partake in Gerhig’s journey. Last summer, Gehrig qualified and competed at the state level of Special Olympics—Missouri (SOMO). He even earned some hardware! More important than the medals he brought home is the smile that brightens his face when you mention his experience. The sense of belonging he felt from his time at SOMO built his confidence enough to become a member of his high school student council. Gehrig looks forward to returning to our local Special Olympics later this April. Therefore, it is only fitting that this month, we strive to educate the world about autism.

A decade after his first view of the ocean, Gehrig has well over a thousand words. But rest assured, those hands still flap in excitement; Frodo is still by his side, and he is still teaching his parents more than they will ever teach him.

References:

4 paws for ability: Home – 4 paws for ability. 4 Paws for Ability -. (n.d.).

Interacting with autistic people. Interacting with Autistic People | Milestones Autism Resources | Cleveland, OH. (n.d.).

Play unified. Special Olympics: Resources. (n.d.).

What we do. SpecialOlympics.org. (n.d.).