Reading Fiction: 5 Tips to Engage Readers

By Dr. Natalie Fallert

As a retired high school Language Arts teacher, I am too familiar with fake reading, skimming, spark notes, or refusing to read. I often attributed this to laziness, but after spending a year following reluctant readers while working on my dissertation, my perspective on the typical teen’s refusal to read the assigned text changed significantly. I found that many students were either on grade level with reading or were stuck around the 5th-grade reading level. Those on grade level were either disinterested in the book they were forced to read or lacked the skills to interact with it independently. Most likely, the “stuck” kids were products of the shift from elementary to middle school, where teachers stopped teaching “reading.” Unfortunately, these kids still needed to be coached up to reading levels. Yes, they could “read” the words, but the demands of the texts had changed, and without the necessary skills, they didn’t know how to adapt. This is not the teachers’ fault; the shift to content-focused instruction at the secondary level leaves many educators unsure how to address these gaps. Of course, there is a lot more behind this work, but these 5 simple tips will work with any grade or book.

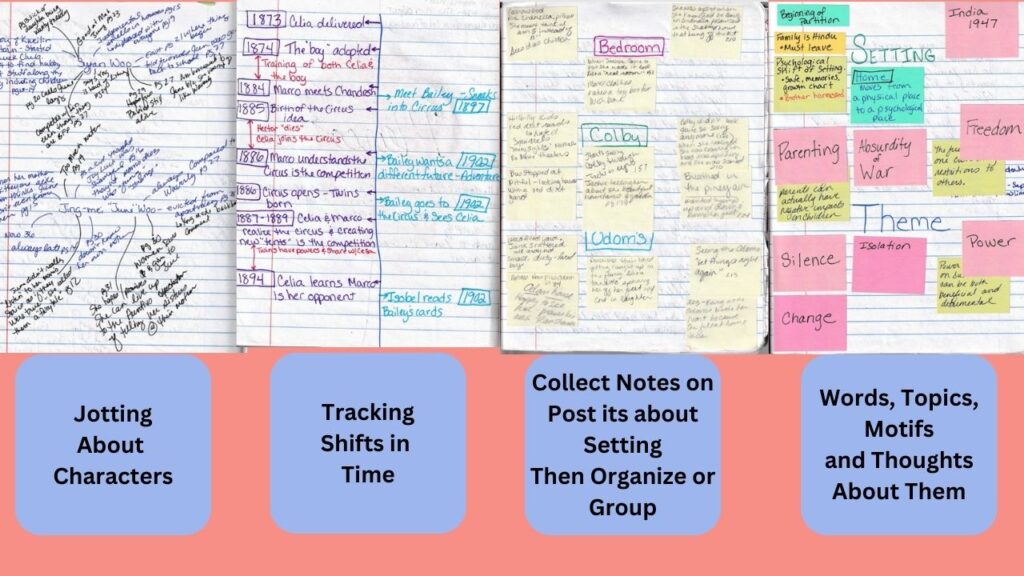

- Between the birth of CCSS and Career and College Readiness, reading expectations for students have become challenging. Reading experts like Allington (Allington et al., 2015) and Hiebert (Hiebert, 2014) are constantly examining students moving up grades and how the texts they are reading become significantly more complex, so it is vital that you intentionally call out these complexities and teach them. Think about texts that your students encounter. How do they become more complex? They may have alternating perspectives or multiple narrators like One of Us Is Lying, Clap When You Land, and Salt to the Sea. They may have shifting timelines like Dreamland Burning and If I Stay. Some books, such as Genuine Fraud and How the Garcia Girls Lost Their Accents, are told in reverse chronology. It is essential to call attention to this and consider offering a variety of ways to track their thinking through notetaking strategies that might work well with that particular structure.

- After students have a firm layout of the structure of their book, the easiest entry point for reading fiction is to pay attention to the characters. All books have characters, and those characters will play a significant role in any type of analysis a teacher wants a student to do about their reading. Teach kids ways to examine their characters and provide ways to collect and organize their notes and thoughts around those characters. Consider looking at character traits, responses, interactions with other characters, pressures that might be weighing on them, and what motivates them. These topics could become mini-lessons teachers model in shared texts, short stories, or books they have previously read. Consider checking out some of Jennifer Serravallo’s resources, especially her Reading Strategies 2.0.

- All books have a setting that is most likely significant to the text. Historical fiction, fantasy, and dystopian novels rely on the setting to play a significant role in the story’s development. Teach students to look for what is happening in this place, what rules characters have to follow, whether the rules apply to everyone, what happened to make it like this, etc. In most realistic fiction novels, the setting might have more of an emotional or psychological impact on the character. I think about Eliza and Her Monsters, where Eliza, the main character, whose personality and actions change as she moves between her home, school, and her online persona. Again, these could become lessons you teach students through modeling with a shared text.

- My favorite aspect/component/idea is teaching them about themes. Yes, I have been guilty myself of either saying, “find the theme” and sending them off to read, or I have told them, “here (fill in the blank) is the theme; now find evidence to support it.” However, it is so much more powerful for you to teach students ways to find a theme and let them discover it themselves and piece together what the author is trying to say about that theme. You can start by thinking about topics or problems that seem to repeatedly arise. Ask students to track how often these come up and if they are evenly spread throughout the text or clustered in one area. Do earlier topics connect with later ones? How are characters responding to them? Does one set or type of characters or groups react differently than others? Common topics or problems that could be explored and are most likely creeping around in your students’ books are relationships, stereotypes, codeswitching, fitting in, speaking out, injustice, prejudice, racism, microaggressions, upstanders, bystanders, etc.

- The most crucial tip when reading fiction is to routinely allow your students to talk about their books with peers. You should not be leading or even facilitating these conversations. If you have done tips 1-4, place them with partners or in groups of four and let them share their findings and hash out their thoughts. This can be done in less than 4 minutes–too much time can be fatal! In Visible Learning for Literary, the authors discuss the expected gains through fostering quality talk in classrooms and emphasize that this practice is most beneficial for those struggling to comprehend.

- I mentioned notetaking and want to touch on this quickly, but you can read more about it in a later blog. I am a huge advocate for teaching kids a variety of ways to take notes rather than using one system or providing them with a graphic organizer. In Hattie’s metastudy, study skills Notes should be for the student to capture their thinking so they can do something with it later: discuss, write, synthesize, etc. Look at some examples of different ways I have captured my thinking in fictional texts.

Resources

Allington, R. L., McCuiston, K., & Billen, M. (2015). What Research Says About Text Complexity and Learning to Read. The Reading Reacher, 68(7), 11. 10.1002/trtr.1280

Green, S., Sanczyk, A., Chambers, C., Mraz, M., & Polly, D. (2021). College and Career Readiness: A Literature Synthesis. Journal of Education. https://doi.org/10.1177/00220574211002209Hiebert, E. H. (2014). Understanding the new demands for text complexity in American secondary schools. In M.C. Hougen (Ed.), Fundamentals of literacy instruction and assessment, 7-12 (Chapter 8). Brookes Publishing.